Origins of the name Goddard

by Brian Goddard, Newbury, England, June 1, 2005

Goddard English (Norman) and French: from Godhard, a personal name composed of the Germanic elements gõd good or god, got god + hard hardy, brave, strong, The name was popular in Europe during the Middle Ages as a result of the fame of St Goddard, an 11th-cent. bishop of Hildesheim who founded a hospice on the pass from Switzerland to Italy that bears his name. This surname and the var. Godard are also borne by Ashkenazic Jews, presumably as an Anglicization of one or more likesounding Jewish surnames.

Vars.. Eng.:

Godard, Godart

Fr.;

Go(u)dard Godar(t)

Patrs.: Low Ger.:

Goddertz:

Gaderts (N. Rhineland).

Patrs. (from dims.):

Low Ger.:

Godden, Gudden.

_________________________________________________________

The above extract from “The Oxford Names Companion” 1 is the probably the most learned answer to the question: “Where does the name Goddard come from?” that you will get. However, it clearly does not give the answer when it implies the name was well established in the 11th century but does not go on to explain how it got to that stage. The 11th century saint referred to above, is detailed in the Catholic Encyclopaedia (www.catholic-forum.com), as: GODEHARD

Also known as

:Godard; Gothard; Godehard the

Bishop; Godehard vescovo

Memorial

: 4 May (Saints Day)

Profile

:His father worked for the canons of

Niederaltaich. Godehard joined the canons, and became their provost. Helped

reintroduce the Benedictine rule at Niederaltaich, which then sent abbots to

Tegernsee, Hersfeld and Kremsmunster to revive the Rule of Benedict. Bishop of

Hildesheim in 1022.

Born

about 960 in Bavaria -

Died

4th May 1038 -

Canonized

by Pope Innocent ll in 1131

But the true origin of the name Goddard is probably hidden in the runes. Runes were angular characters of the alphabet in use amongst Anglo-Saxons, Norse and other ancient Germanic peoples between the 3rd and 10th centuries. Runes were derived from the Greek or Roman alphabet with some additional symbols and modified for cutting or scratching on stone, metal, ivory or other hard substances used before parchment or paper.

Although much of our modern language comes from a mixture of the languages of the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings, very few Christian names do. However, when you look at surnames, there is much more evidence of our Saxon and Viking past. The Anglo-Saxons distinguished between two people with the same name by adding either the place they came from, or the job they did to their first name, for example a man named Edward who was a tailor would be known as Edward the Tailor, or just Edward Tailor. Many of our modern surnames are actually occupational names - Bowyer, Baxter (baker), Baker, Weaver, Fisher, Fowler, Hunter, Farmer, Fletcher, etc.

Many Vikings also had a nickname which was used instead of their family name. Giving a nickname was like naming a new-born baby; it created a special tie between the name-giver and name-taker. The newly named person could claim a gift from the name-giver, either a present or a favour, even if the name was derogatory, which many of them were. Nicknames sometimes went by contraries; a man with swarthy skin might be called “the fair”; an unusually tall man might be named “the short” ( much like “little John” in the Robin Hood stories ). Few Viking women appear to have had nicknames, and most of those that did described the woman's wisdom, beauty, wealth or speech habits. (Perhaps the less complimentary names never made it into the sagas, for fear of retribution of the physical sort? )

The translation of many of the Norse sagas show that there were many Viking names of wide variety and complexity, here are some starting with the letter G - Gardar Svafarsson, Gauk, Gauk Trandilsson, Geirmund, Geirolf the Warrior, Gest Oddleifsson, Gisli Sursson, Gizur Teitson, Gizur the White, Glum, Gnupa-Bard, Grani, Grim, Grim Kamban, Grjotgard, Gudbrand of the Dales, Gudleif Arason, Gunnar Hamundarson, Gunnars Holt, Gardar, Gaut, Gauti, Gautrek, Geir, Geirrod, Geirthjof, Gellir, Gest, Gilli, Gilling, Gisli, Gizur, Glammad, Glum, Godfred, Godi, Godmund, Godord, Gold-Thorir, Gorm, Grettir, Grimkell, Grubs, Grundi, Gudlaug, Gudmund, Gudrod, Gudrodar, Gungu-Hrolf, Gunnar, Gunnbjorn, Gunnlaug, Gurd, Gusir, Gust, Guthfrith, Guthorm, Guthrum.

These are just a

few of those G's

that made it into the Viking sagas worthy of translation, there must be many

more lost in history. As may be seen, even on this minute selection, there are

several contenders for the origin of the name “Goddard”

without the contortions of spelling and misinterpretation offered by several of

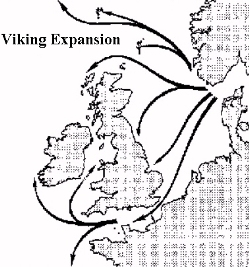

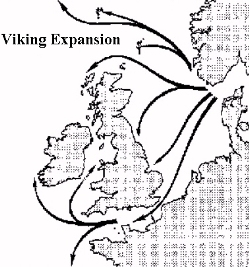

the name researchers. The Vikings were venturesome seafarers. From Denmark,

Norway and Sweden they spread through Europe and the North Atlantic in the

period of Scandinavian expansion (AD 800-1050) known as the Viking Age. Although

they are often thought of primarily as raiders, the Vikings were also traders,

explorers and settlers. Behind them they left a legacy not only of

archaeological remains, but also of family names, place names and field names.

These remains can be found in local dialects and customs, in folk tales and oral

traditions, and of course in the genetic make up of the local people themselves.

The Vikings influenced a larger area of the globe than ever the Roman Empire did

in its day. Vikings occupied land from Kiev and Novgorod in Russia, parts of

Turkey, throughout the north Mediterranean countries and the Iberian Peninsula.

They crossed the Atlantic where they colonised the Vinland settlement on the

coast of North America for 15 years and they colonised and christianised both

Iceland and Greenland before conquering Ireland and the rest of the British

Isles and Norway.

The name “Goddard” probably entered the British Isles with the raids by the Viking of Denmark which started in 789. In 840 they founded the city of Dublin and by 1013 the Viking Danes had conquered England. In 1016 the Danes under Cnut (Knut or Canute, as you will) ruled England. When the Viking invaded they brought their language with them – Old Norse. Since the Vikings came from different parts of Scandinavia they all used their own dialect of Old Norse although the basic language was the same (much like modern English, American and Australian ). Old English and Old Norse were in many ways similar since they had both developed out of the same language ( like modern English and German), and the language spoken in Denmark at this time was mostly understandable by the Anglo-Saxons and vice-versa and there were many words that were similar in both languages.

The Normans are frequently but mistakenly assumed to be of French origin, but they too are more accurately of Viking origin. Thorfinn Rollo, the descendant of King Stirgud the Stout the Viking who landed in the Orkneys and Northern Scotland about the year 870 AD, landed in northern France about the year 940. The French King, Charles the Simple, finally conceded defeat after Rollo laid siege to Paris and granted northern France to Rollo. Rollo became first Duke of Normandy, the territory of north men. Duke William who with his invasion force defeated the English army in 1066 was descended from the first Duke Rollo of Normandy.

By AD 1000 parchment was the predominant material for retaining information and there are hints from documents of the period that there were Goddards living in the British Isles before the Norman Conquest. With two established market towns of Goderville in Normandy and Godarville in Belgium (both of which may owe their names to different ancient families of Godord or Godard), and the German Saint on the Swiss/Italian border, one can have some idea as to the extent to which the Goddard name, with only minor language variations, was established by 1000. And of course there was Godard “of Antioch” the sheriff in London in 1195 and William Goddard “of Amiens”, a merchant in 1395.

Since the Vikings laid the trail there has been a continuous flow of Goddards, both into and away from the British Isles, to virtually every country in the world. Migration has always peaked at times of stress due to privation, or political and religious duress, with Goddards coming in with the Huguenots and the French and Prussian Wars, while leaving with the Civil War, the Irish potato famine and the agricultural revolution. But, above all, the Goddards have a history as travellers, traders, soldiers, sailors, missionaries and latterly engineers, frequently finding a permanent residence in their country of work at the end of their contract.

There is a common misunderstanding that all the various Goddard families have been here since medieval times. Many have, but there is significant evidence showing that there are Goddards who have come to Britain to work and to bring up their families in much more recent times. There is, for instance, the will for Anthony Goddard, a merchant from Holland who died in London in 1572, leaving property to a son John. In 1618 a Privy Council report gives the names of “strangers” in the city of London and lists one John Goddard, who had been born in Paris and who had arrived in London in 1615. He was then said to be working in Farringdon as a clock-maker, although a Catholic, he had sworn allegiance to the king in 1618. His family, it appears, from trade directories, were still working in the clock-making trade, in London, over 150 years later. These families were followed much later by the wine merchant Goddards from France, who can still be found in this trade today.

Goddards appearing in early documents include Godardus de Clackesbi of Lincolnshire in 1160, Robert Godard in Hampshire in 1208, Wilfrich Godard of Ely Norfolk 1221. Scotland also had its fair share of Goddards, although the name is very rare there now, but we had Robert filius Godardi at Peebles 1262, William Godarde was a witness on a charter document in 1320. Peter Godard “bruer” a Scot, had letters of denization in England in 1480, while James Godard was a burgess of Aberdeen in 1493 and Peter Gouderd, a feltmaker, was made a burgess of Edinburgh in 1734.

A mistake frequently made, by many people doing the genealogy of their family, is to claim that their predecessors came over with William the Conquerer. In all but a minute number of cases, all this shows is that they do not have an understanding of the subject. In the few cases where it is true, they would not be doing the research themselves they would have staff answerable to their private archivist for that! There is little documentary evidence to say that any Goddards arrived in 1066. However, there is a record 2 of Rogerius Godardi, or Godardus and his uncle Ernulfus, relatives of Roger de Buslei, one of the most influential Norman Barons, selling the tithes they had inherited on the Buslei estates at Drincourt (now called Neufchâtel-en-Bray) in the winter of 1065, to pay for equipment for themselves and their retinue to join Duke Williams expedition to England. But nothing further was heard of them, Roger de Buslei apparently did not reward them, although as the third highest ranked baron in England, until his death in 1099, he would have been in the position to do so. The Domesday Book also lists “Godard, Jocelin Fitzlambert’s man” at Tealby in Lincolnshire, but who is to say that his family were not already established in this area before the conquest.

Apart from the “de Goderville's” of King John's time, (also documented as de Godarville, or de Gardeville), who may or may not have been so named before they came to Britain in the 12th century, Sir Hugh and Hugh, father and son, in the Chester area, Sir Walter of Wiltshire and Ireland, a cleric Eustace, presented to the living at Wendlebury, north of Oxford, by Sir Walter, (were they brothers?), and Robert a treasurer at Salisbury Cathedral, the Goddards, particularly “high born Goddards”, are notable by their absence from written documents. Even these Goderville's were probably not all related to each other, as no document has been found that mentions a relationship between any of them. But, from the evidence of land ownership it is almost certain that Sir Hugh and Sir Walter were close relatives.

By 1282 the then Sir Hugh of Cheshire, grandson of the original Goderville, is now called Goddard. The last hereditary knighted member of this family was Sir Robert Goddard, an Alderman of London who died in 1604 without a male heir. Until the ending of the feudal system there was little requirement for surnames for any but the highest in the land, and indeed, they were usually known by their titles. By the end of the 14th century the military justification for “feudal tenure” had declined and the development of “royal justice” contributed to the decline of the private jurisdiction of the feudal lords. With the introduction of this remote rule of law came the requirement for better identification of individuals, this was answered by the introduction of surnames.

By the 16th century still more personal accountability was required which was made possible by the enforced introduction of the Parish Registers, using the fixed surnames which in Britain, (not required by law in Wales until 1850), had already become normal practice. Until surnames were fixed direct taxation and control could only be carried out by those who knew the individual by sight. This meant that while the feudal law system was used taxation and justice, all local criminal and civil law, had to be dictated by the feudal lord of the manor, or in their increasingly frequent absence, by his stewards.

The introduction of the parish records registering names at the birth, marriages and the death of individuals allows the genealogy of the Goddards and others to be traced back in some cases to the early 17th century. It is surprising that there such a number of Goddard families, in unrelated groups, are to be found in the earliest of these records, dotted throughout Britain. These families have in many cases have, obviously, been established here for centuries. The lack of contemporary documents from the 11th to 16th centuries naming individuals can only mean that virtually all those Goddards entering the country were of the level of foot soldier, retainers, colonisers, tradesmen or domestic staff, or others possibly seeking asylum in Britain. In the time since the Norman invasion a stream of Goddards have entered Britain from many European countries and Ireland and over the centuries a few have risen to the upper echelons of society, but only by hard work, the acquisition of land, or by luck.

With a name like Goddard there is a vague chance that you can trace your family tree back to the early parish records, but not beyond. However, if you had the surname of Jones, there is no chance that you could decide from which Viking “son of Jon” your line descends!

Published by Oxford University Press in 2002. ISBN 0-19-860561-7

Miscellanea Genealogica et Heraldica Vol II Fourth Series. 1908 – Society of Genealogists London and other libraries